The Landis v. Tailwind Sports Corp. 234 F.Supp.3rd 180, 186-90 i.e. USPS v. Lance Armstrong. This case, in addition to being interesting, illustrates how complex damage computations can become. There are at least three questions which should always be asked when reviewing your own or the opposition’s expert opinions relating to speculation, methodology and expert qualifications.

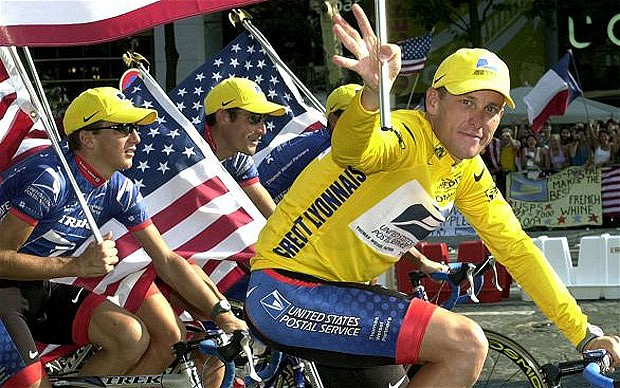

The Case: The US Postal Service (USPS) sponsored Lance Armstrong’s cycling team between 1995 and 2004. During that time, the USPS paid approximately $32 million to support his cycling team and Armstrong received salaries of approximately $17.9 million. The agreement required the cycling team to comply with the anti-doping regulations of the sport’s governing bodies. During the time of the sponsorship, Armstrong was found to have illegal substances in his blood in violation of the agreement.

The Damages Claim: The government sought to recover approximately three times the amount paid for sponsorships – $100 million under the False Claims Act.

The False Claims Act: The False Claims Act (FCA) is a Federal statute, 31 U.S.C. Section 3729(a) and any person found guilty of violating the FCA is liable for civil penalties plus three times the amount of damages.

Difficulty in Determining the Measure of Damages: The unique aspects of the case made the application of traditional damage measurement methodologies difficult, if not impossible.

The publicity value the USPS received from the sponsorship was obviously the most difficult amount to determine. Both sides called in experts to testify.

Armstrong argued that there were no damages because the USPS received value in excess of the $32 million paid in sponsorship fees. Afterall, Armstrong was a seven-time winner of the Tour de France and enjoyed a massive fan base.

The USPS argued the benefits received from sponsoring the team were reduced or eliminated by the negative publicity created by the investigation and disclosure of the team’s illegal acts.

The framework to be allowed at trial in this case for determining the amount of damages was:

- the amount paid by the USPS for sponsoring the team, less

- the publicity value the USPS received from the sponsorship

Armstrong’s Daubert Challenges: Armstrong mounted a Daubert challenge against the USPS experts claiming among other things:

Question One – Speculation: The USPS experts’ calculations of possible monetary damages were based entirely on speculation. See Kenford v. County of Erie, 67 N.Y.2d at 261-262 “the multitude of assumptions required to establish projections of profitability over the life of this contract require speculation and conjecture, making it beyond the capability of even the most sophisticated procedures to satisfy the legal requirements of proof with reasonable certainty.”

Depending on the circumstances and degree of speculation, this can often form the basis for a reasonable challenge.

Question Two – Methodology: The USPS experts did not rely on proven damage theories, i.e. the “but for” methodology, a yardstick measurement approach, or a sales projection method. It was difficult here to use a “generally accepted methodology” because the nature of the damages was so unusual. Armstrong’s argument was essentially that the experts’ methodologies did not produce reliable results.

Armstrong also argued that even with permissible damage theories, the USPS experts’ testimony was irrelevant because it would not give the jury a means to quantify the damages. The USPS replied that there was certainty that the damages occurred, and, in that case, damages may be based on reasonable estimates.

As stated above, the USPS’s position is that damages calculated on reasonable estimates are proper. “The wrongdoer is not entitled to complain that they (damages) cannot be measured with exactness and precision” see, e.g. Story Parchment, 282 U.S. at 563. Also see Palmer, 311 U.S. at 561 “Certainty as to amount goes no further than to require a basis for a reasoned conclusion.”

Question Three – Expert Qualifications: The USPS experts’ qualifications were inadequate. One was challenged because he had no formal education in the valuation of negative publicity. We hear similar challenges raised in almost every dispute.

All Armstrong’s above Daubert challenges failed. The case settled before trial and the experts never had the opportunity to present their interesting damage measurements to the jury.

The damage measurement complexities in this case highlight the importance of hiring experts who can create and defend their reliable, relevant and, when required, creative methods. We can help you, give us a call.